Ahead of the G20 summit the India China border dispute is explained

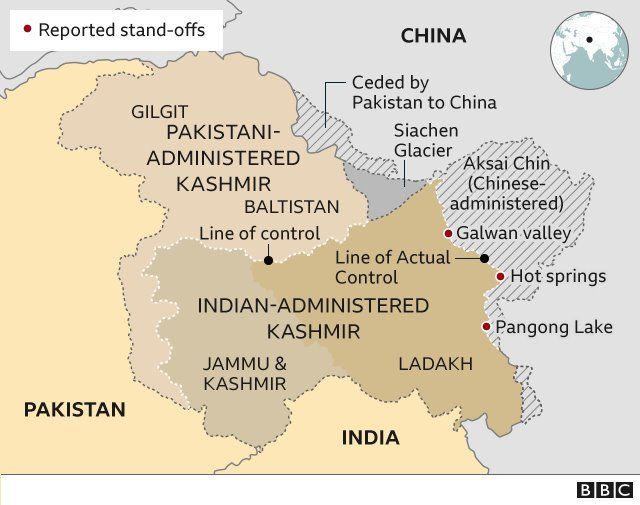

The main dispute is the 3,440km (2,100-mile)-long disputed border.The two nations are also competing to build infrastructure along the border.

There are strong tensions at the border level despite military level talks. Soldiers suffered minor injuries at the tawang sector of Arunachal Pradesh.

More recently another face off took place India's Sikkim state, between Bhutan and Nepal

It is beileved that In September 2021, China accused India of firing shots at its troops. India accused China of firing into the air.If true, it would be the first time in 45 years that shots were fired at the border. A 1996 agreement prohibited the use of guns and explosives near the border.The same month, both countries agreed to disengage from a disputed western Himalayan border area.

The two countries have fought only one war, in 1962, when India suffered a humiliating defeat.But simmering tensions involve the risk of escalation - and that can be devastating given both sides are established nuclear powers. There would also be economic fallout as China is one of India's biggest trading partners.

Led by Northwestern University, Technical University of Delft in the Netherlands and the Netherlands Defence Academy, the authors assembled a new dataset, compiling information about Chinese incursions into India from 2006 to 2020. Then they used game theory and statistical methods to analyze the data.

The researchers found that conflicts can be separated into two distinct sectors: west/middle (the Aksai Chin region) and east (the Arunachal Pradesh region). While the researchers learned that the number of incursions are generally increasing over time, they concluded that conflicts in the east and middle sectors are part of a coordinated expansionist strategy.

By pinpointing the exact locations lying at the root of the conflict, the researchers believe deterrents could be established in these specific areas to defuse tensions along the entire border.

The study, “Rising tension in the Himalayas: A geospatial analysis of Chinese border incursions into India,” was published today (Nov. 10) in the journal PLOS ONE.

“By studying the number of incursions that occurred in the west and middle sectors over time, it became obvious, statistically, that these incursions are not random,” said Northwestern’s V.S. Subrahmanian, the study’s senior author. “The probability of randomness is very low, which suggests to us that it’s a coordinated effort. When we looked at the eastern sector, however, there is much weaker evidence for coordination. Settling border disputes in specific areas could be an important first step in a step-by-step resolution of the entire conflict.”

A world-renowned expert in AI and security matters, Subrahmanian is the Walter P. Murphy Professor of Computer Science at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and a Buffett Faculty Fellow at Northwestern’s Buffett Institute for Global Affairs.

The military stand-off is mirrored by growing political tension, which has strained ties between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping.Observers say talks are the only way forward because both countries have much to lose.

In the 15-year dataset, the researchers noted an average of 7.8 incursions per year. The Indian government’s estimates, however, are much higher at 300 per year.

“Although the Indian government publicizes these numbers, we don’t have the details behind them,” Subrahmanian said. “They might be counting a series of temporally proximate events as several different incursions, whereas we count them all as part of the same one incursion. But when we plotted our data and their data on a graph, the curves still have the same shape. Both curves show that incursions are increasing — but not steadily. They rise and fall, while still trending upward.”

Although hotspots occur throughout Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh, the researchers’ game-theory analysis indicates that only the incursions in Aksai Chin are part of a coordinated effort. Building on insights from game theory, the researchers predict that China is trying to establish permanent control over Aksai Chin by allocating more troops for a longer period of time than India.

“China grabs a little bit of territory and then a little bit more until India accepts that it’s Chinese territory,” Subrahmanian said. “There is a saying: ‘Keep the pot boiling but don’t let it boil over.’ China takes small pieces of land, but keeps it under the threshold of where India would counter-attack. But, over time, it becomes a bigger piece of land.”

“By studying the number of incursions that occurred in the west and middle sectors over time, it became obvious, statistically, that these incursions are not random.”

– V.S. Subrahmanian, computer scientist